Voyage on the National Mall in Washington, DC. The Sun and inner Solar System are seen in front of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Visible in the distance are the Washington Monument, and the Smithsonian Castle where Pluto is located. Credit: ©Smithsonian Institution, Eric Long

A physical model is a replica of something typically too large or too small for us to easily observe directly. As a learning tool, a good physical model is usually constructed at a size that a person can easily manipulate with their hands so they can explore characteristics of the real thing as a model. Examples are a globe of the Earth, a street map you keep in your car, or a classroom model of DNA. The bridge to the familiar here is representation of the real thing at a size we can literally handle, and explore.

The central element of the Voyage exhibition is a physical model of the Solar System at the one to 10-billion scale. The real Solar System is exactly 10 billion times larger than Voyage. The sizes of the Sun, planets, and moons are represented on the same scale as the distances between these objects, which provides visitors the stark reality of small worlds in a vast space.

In addition, the storyboard for each planet includes a whole disk photograph of the planet next to a photograph of the Earth at the same scale. These photographs are 2-dimensional physical models, and they allow the visitor to understand the relative size of the planet compared to familiar Earth.

Physical modeling is also heavily used in the grade K-12 Voyage lessons. At the elementary level, its use is as simple as a student drawing a view of their home from the front door, from a tall building, from an airplane, and from space.

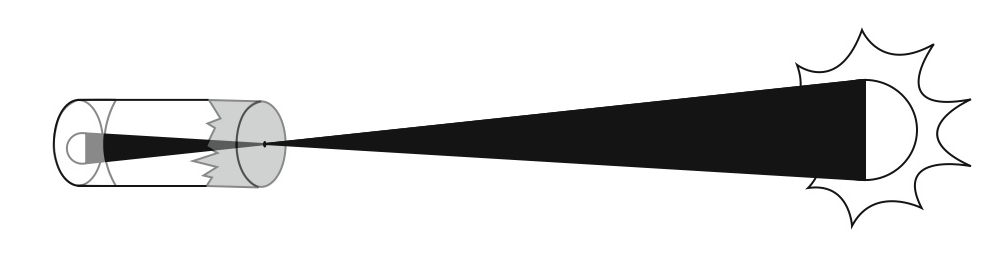

At the middle school level, the student measures the distance to the Sun with a paper towel tube, small squares of aluminum foil and graph paper, a couple of rubber-bands, and a pin. A ‘pinhole tube’—a simple camera—pointed to the Sun creates a small image of the Sun—a model of the Sun—on the screen at the back of the tube. The image of the Sun and the length of the tube represent a physical model of the real Sun and the Earth-Sun distance (because the two black triangles below are similar). By calculating the number of model Suns side-by-side that would span the length of the tube, the student is actually calculating how many real Sun’s side-by-side would span the real distance between Earth and Sun. Elegant inquiry-based science education doesn’t require a sophisticated laboratory apparatus.